Chapter 3: Strategic Planning and Service Improvement

Chapter 3: Strategic Planning and Service Improvement

The people who are most affected by a service or organisation should be the key stakeholders in influencing how it is shaped. There are a myriad of ways to ensure that children and young people are involved in service design and strategic planning – from service-level feedback, to recruitment, to strategic planning, budget setting, and evaluations.

Involving children and young people in these ‘higher-level’ decisions can be incredibly insightful. It can help to identify problems that no one realised, understand where good practice exists that should be maintained, and ensure that young people’s lived experiences are understood, respected and valued.

For example, some messages that were pulled from the 2021/22 HSCP participation survey were:

‘We would like to be able to access help earlier rather than having to wait until any problem is really serious’

‘We would like better communication between services so that less of us fall through the gaps and we don’t have to keep repeating our stories’

If these messages are listened to, it would mean investing in preventative approaches and ensuring that children and young people can access them at the right time. It would also mean re-enforcing the message of the important of multi-agency working, and finding innovative ways to prevent children having to repeat their stories.

Much of what young people pick up on in the survey is preventative approaches, and actually these are the ones that can improve a service longer-term and aid affective management of both time and resources. It’s also an aspect that young people feel particularly passionate about and have incredibly insightful ideas about – hence the importance of really meaningful participation activities. Where young people take up the mantle of change and drive the projects, the change can be far faster, smarter, and more impactful.

‘It feels like we aren’t really taken seriously when there’s something we care about’

Gathering feedback on services can be as quick, lengthy, small, large, frequent as a service needs it to be. Flexibility is key not only to meet the demands of inclusion (see Section 1.5) but also to ensure that the scope fits the remit needed by the service. It is also essential to understand what difference your service is making.

‘We need to understand how to voice concerns we have about ourselves or others, especially if we are not in education/employment’

HIS (Healthcare Improvement Scotland) has an exemplary resource in terms of different techniques. Just a few are highlighted here:

‘To actually listen to them, just because they’re young doesn’t mean they’re not smart enough. Work as a team and give the chances and opportunities to the young people’

One of the simplest methods of gathering views is the “Dot voting’ way. This is being trialled at St. David’s PRU in Hereford to create fast snap-shots that can then be used to improve student service. Topics range every few weeks from ‘How do you want to be rewarded for good behaviour?’ to ‘’What should we offer for lunch?’

The voting board is set up next to the canteen hatch and a voting ‘dot’ given with each drink/piece of toast. As it is quick, easy and accessible it enables young people that wouldn’t normally necessarily participate to have a say.

There are pockets within society that are already well geared towards youth participation. Schools (as seen above) and youth organisations/voluntary sector are at an advantage because they work purely with young people. They therefore have a body of young people – be it a school council, or a youth scrutiny group, that are used to getting involved. Collaboration between service providers (the ‘multi-agency’ approach referred to throughout) is therefore hugely beneficial.

The work between Herefordshire Healthwatch, Strong Young Minds and John Kyrle High School and Sixth Form Centre is an excellent example of this. See Youth Voice – How should mental health spending be invested?

‘We need to be asked more questions and have the questions be more varied to allow people to share important views they otherwise would not have been able to share’

Arguably, one of the biggest contributors to the success of engagement is surroundings and atmosphere, and therefore choice of place and activity is paramount.

Engagement in anything is reliant on it being enjoyable, as well as it being worthwhile, so if the activity/venue/plan is appealing, you are automatically boosting the chances of positive and meaningful engagement.

This was put into excellent practice recently by Talk Community Herefordshire. See the video below to see the activities in action and the impact the project had.

Talk Community Herefordshire’s ‘Let’s Talk Children and Families survey’ aimed to capture the views of children, young people and their families living in the county to aid understanding of what works really well in Herefordshire and what would make the county an even better place to live. By combining the survey with a range of entertaining activities and taking it out to communities in settings that people are comfortable in, it meant that take-up was higher than normal, as was the sense of community.

The list of opportunities to share views and enjoy every second was extensive: circus skills, art classes, Glo Parties, Kids Kitchen, Talking Sofa, Kids eat free after school, Hereford FC Bull, messy play, stay and play, party disco, team games, sensory play, DJ, quiet zone for children with SEND, Big Family Lunch, bikes and soft play, craft stalls, pancake races.

With the uncertainty that covid-19 has brought over the past few years, it’s hardly surprising that a lot of agencies have turned to digital platforms not only for their day-to-day work, but also for the purpose of youth participation.

Young Minds has developed a comprehensive booklet on Digital Engagement in Participation which has tips on how to engage, how to make it interesting and also how to tackle safeguarding from an online perspective (See more on this in Section 4.3).

‘Give me questions I understand’

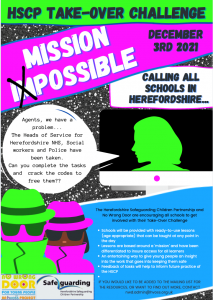

A recent HSCP Take Over Day Challenge showed the benefit of this approach as 9 schools and voluntary groups took part. The numbers at these ranged from a group of 8 neuro-diverse 16-25 year olds (NEET), to over 300 participants in one school. A broad route like this also enabled the partnership to ensure inclusion with one in five young people in Herefordshire with SEND attending mainstream schools. In some of the schools that took part this was higher, for example 100 students at Hampton Dene Primary school which has an on-site special educational needs and/or disabilities resource base took part and students from the RNC and PRUs fed ideas into the initial concepts.

The HSCP Take Over Challenge aimed to gather the Voice of the Child but in a format that was very specific to the strategic needs of the partnership and service development, rather than gaining a general commentary on service provision. The potential direct link between voice of the child and meaningful change is therefore evidenced well here.

Four lessons were devised collaboratively with young people to go into schools across the county. At the start of each, a video explaining the challenge and the work of the HSCP was shown. To raise the profile of the service, as well as focus on its key agencies, it also featured Heads of Service describing the day-to-day decisions they have to make. (See the video link below)

Lesson One (KS2): Create a ‘Safeguarding Superhero.

Lesson Two (KS2/3): Generate material to advise parents/carers on how to keep young people safe.

Lesson Three (KS3/4): Generate material to advise young people of what healthy relationships look like and what to do if support is needed.

Lesson Four (KS4/5): Debate, prioritise and justify budget-spending.

‘Make whatever you do exciting’

There is significant scope to use data findings to highlight areas for development, adjust service and provide training. Where the use of information becomes even more valuable is in the creation of resources and systems that come directly from what young people have said.

Can you use material gathered to do the following (for example)?

Input from young people would therefore be feeding in to adult-led change, giving them an element of ownership over processes.

Healthwatch Herefordshire’s Youthwatch Project is an excellent example of the power of young people engaging with issues, asking questions and seeking answers from adults, therefore progressing the service.

Youth-led change can, arguably, have even more impact. The information gathered from young people, is then interpreted/given context by young people, projects addressing it are devised by young people, acted on by young people and provision is adapted/improved for young people. The advantages to this are vast, but as the coloured words show, essentially it is a system that gives ownership to young people of projects they will feel incredibly passionate about as, other than at the initial ‘gathering’ stage, nothing is merely done to the young people. It is all either by or for them.

This approach may need a good degree of professional facilitation, and it is important that the young people are guided to be focused and realistic in how they develop recommendations (i.e. SMART), summarise findings, etc. With good training, building of skills and a bit of guidance, projects like this can become sustainable and, as the adults loosen the reigns, the less time is needed from them to facilitate.

In 2019 the issue of rising knife crime and fire-arm incidents was identified in Coventry. West Midlands Police and Crime Commissioning office donated £5000 for a project to find out what young people needed and 18 years old Tyler Campbell came up with the idea of ‘Fridays’.

With pledges of support and money from local businesses and universities he was able to establish a club that keeps 15-17 year olds safe and off the streets. Young people are signed up with parents/carers’ permission and escorted safely to and from the venue. Upstairs is entertainment; DJs, barber shops, activities, and downstairs the focus is on advice, life skills and guidance; mentoring, CV writing, even courses like FEEL (Fridays Empowerment, Entrepreneur and Leadership Programme).

There are now more than 200 young people engaging with the project each week and they’ve just received the National Crimebeat Award.

‘Take them into account more, not just well-being and rules, but aspirations and interests, these are huge factors for young people feeling happy and content with their lives and surroundings’

‘Be open to our suggestions, give us more credit than we’re given. We know what we need as well as anyone else’

To embed any form of change, structures and systems need to be in place to foster an organisational culture with a clear ethos.

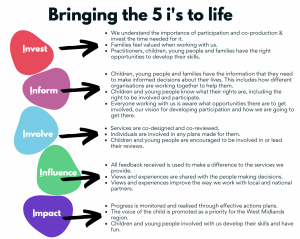

The West Midland’s 5 i’s are a framework to think about participation within the whole system.

How it is actively used in conjunction with tools, exemplars of good practice and, most importantly, continuing input from young people will really define how embedded and successful it becomes.

It’s also often easier to embed a culture/mindset if there is a mutual and tangible goal. The National Youth Agency’s Hear by Right model allows that for a whole service.

The process is explained in the NYA Hear by Right Framework.

The core values and impact of entering such a scheme are also shown in the young person made (and very quirky!) video from the Hear by Right Gloucestershire team.

‘It felt like my voice mattered and somebody actually cared enough to listen’

Service improvement can certainly be driven by having the right professionals in the right roles, and having young people as a part of the recruitment and selection process can aid this. This is especially the case given that young people know what their needs are in terms of what makes a good professional, but also as so much of the role is relational, seeing a potential candidate with young people is really important.

The extent of the role played by young people in recruitment can vary; they could do as little as give candidates a tour of the building (still enough to gauge the way they talk to young people), or sit on a panel, or even come up with some questions. Why not let them choose an aspect of the criteria based on what they look for from a good candidate?

The Plymouth Young Safeguarders have a clear list of ‘wishes’ for professionals that, for example, could form the basis of a question:

- We want professionals to be easier to contact.

- We want professionals to be on time, as they expect us to be.

- We want professionals to be properly trained and for us to be involved in the training.

- We want professionals to ask us what we need and not to assume.

- We want professionals to do what they say they are going to do, to listen and stand up for us.

- We want professionals to sue words we understand.

- We want professionals to reassure us something is being done and tell us how long it will take.

- We want professionals to understand when we need to talk to them one-to-one.

- We want professionals to ask us ‘do you feel safe?’

- We want professionals to respect us and how we feel.

Some agencies go even further, so not just playing a role in recruitment and selection but being a regular advisory body. For example, the Children’s Commissioner for Wales has a young people’s advisory panel. It outlines the work they do as the following:

Continue to the next chapter: Chapter 4 – Ask, Listen, Act, Feedback