As seen in consultations with young people across the county, there is a distinct gap between the support available and their perception of that. Quite often young people will present the view that ‘there’s no help around’, ‘professionals don’t take any notice of what we say’ and, most disheartening of all, ‘professionals don’t care about us’.

This was, unfortunately, typified by one of the anonymous comments in the survey:

‘I opened up to them about a serious matter and they didn’t do anything about it and referred me to a support worker who hasn’t actually been put in place after months. Made me feel very invalidated as I don’t like to open up very much and it clearly wasn’t a serious matter to them as they did nothing to help’

Despite this view, there is much good work happening to listen to young people and improve support for them. Professionals consistently fight for funding for projects to improve levels of support, they attend course after course to improve practice and respond to issues that arise, they choose to work in an area that is incredibly hard because they care deeply about young people. So why the disjoint?

Part of it is down to perception and the tone of what’s being delivered, rather than the service provision itself (see section 1.2) but a large proportion of the mismatch lies with the fact that young people simply don’t know about the work that goes on. The implication of this is huge. Children who are in need may not access the relevant support, others may not even see a point in trying and professionals can feel misunderstood and, to a degree, attacked. In terms of participation and Voice of the Child the implication can, likewise, be stark. If they don’t see/hear about the difference their opinion makes, why would they continue to bother to contribute? It can, sadly, be perceived as a tick-box exercise rather than something of value that leads to definite change.

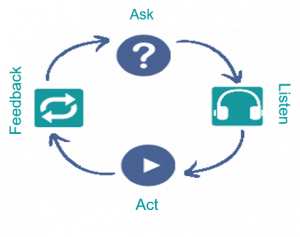

In order to resolve many of the misperceptions discussed on the previous pages, the need for a culture shift away from ‘Ask and listen’ and even ‘Ask and listen and act’ to ‘ACT, LISTEN, ACT AND FEEDBACK’ is a real necessity.

Processes to mitigate against this are relatively simple, as other young people identified:

‘We need regular updates when we’re involved in services’

We would like to know how our feedback is acted on/used

‘Services told me they would be in contact and then immediately closed my file, so a better follow up would improve the service’

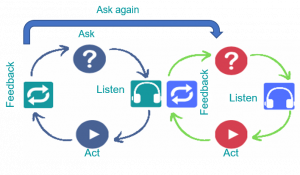

It’s also important not to view the looped model in isolation. It’s completely logical given that young people, their views and needs evolve over time, that so should the process of participation and Voice of the Child. Only then can service provision evolve.

For example, model A shows a successful looped model, but only in isolation…

An accompanying analogy may be something like young people are asked where dangerous areas in Herefordshire are, the police and exploitation team listen, and then act to create a rotating patrol around those hot-spot areas. They feed the changes back to the young people that they initially asked, as well as feeding back to the community at large. This would certainly be a participation success.

However, if that was then the end, what if the hot-spots changed?

Or what if, as result of the previous action, young people were now finding interior locations – stairwells, school toilets, on buses? If the process of asking again is not done, then the same problems are continually faced and services fail to keep up with evolving behaviours.

Model B is therefore a far more advanced and progressive model in terms of service development.

Instead of having a few quick wins, you have a service that constantly evolves and constantly speaks for young people, which then has far greater long-term benefits.

One example of evolving service is that of Hereford FC and their Generation Z project. They had previously run boot camps in the holidays and Going for Goal schemes for young people, integrating football and agencies such as West Mercia Police in response to needs identified by young people. However, as projects ended and feedback was sought again, young people said they’d loved it, it had kept them off the streets, it had given them something to do, but what now?

Instead of closing the project on the basis that aims were met and all had benefited, they refocused on the ‘what now?’ responses from young people and have now established a youth night called Generation Z (see link to article to the left).

There are many examples of great engagement and decisive child-centred service improvement occurring, but if it is only reported in a word document on a website or emailed to schools and ends up at the bottom of an inbox, the likelihood is that young people won’t know.

Using ‘youth-friendly’ mechanisms of feedback is therefore essential, thinking about language, design, placement and means of dissemination.

Getting the language-base right, whether orally (as discussed to a degree in section 1.2) or in written form, can be difficult. One anonymous young person’s guidance shows the complexity:

‘Don’t treat them like idiots and small children and don’t treat them years above their age but actually treat them their age like and equal. Don’t talk down to them and don’t act like they’re stupid, make sure you’re understanding and patient and won’t get offended if they yell, obviously they’re going to get defensive if you’re treating them like they’re five. If you’re working with a younger person like eight and under don’t act like they’re adults, they’re not, they’re kids – for all you know they could be scared of talking to some strange person they don’t know. Don’t over-act anything, be natural and nice, don’t be over nice just talk to them like a human. If they’re over nine they are old enough to be treated like an adult, tell it straight, say it how it is – at that age no-one needs you to speak like they don’t have a brain cell – yeah, they might be a kid, but don’t sugar-coat it at any age. Be calm and more careful with eight and under but not like they’re dumb ‘cause they’ll shut down, won’t talk to you and nothing will happen’

As seen, often young people will react differently in different circumstances and this may be age-based but more likely just down to the individual. The safest approach, always, is to simply check readability and tone with a young person before putting it out there. In terms of content, clarity is key, and, again, the best ‘proof-reader’ is a young person.

Font makes a huge difference. Take the examples below. Two are ‘youth friendly’ but even then, it would depend on the age of the young person (pink example would be great for primary age young people, but patronising for older ones for example).

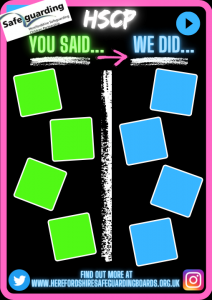

Visual designs also need to be bright, bold, age/ability appropriate and, where possible, branded. If the message going out is that the organisation is listening and acting on the Voice of the Child, then young people need to be able to recognise what the organisation is and that means raising its profile.

Posters similar to this one that have a simple format and are easy to adapt could be used in a variety of ways. For example, whilst there is a lot of remit for use on social media (see next page), it’s also worth thinking about where young people go, where they wait, where they see posters. So, for example, GP waiting rooms, school/college corridors, youth centres, police reception areas, sports clubs, supported housing shared kitchens, council offices etc, etc.

As young people take in information in a variety of ways, and have a variety of preferences, disseminating feedback from projects and outcomes generally in a range of ways makes absolute sense. Section 3.3 outlines some of these, and a website well worth looking at to see how the Voice of the Child can be interpreted in engaging and accessible ways is the Points of View Rural Media project.

Point of View is a project from Rural Media consulting with and sharing the voices of 14-25 year olds in rural Herefordshire, Shropshire and Worcestershire. Young people are empowered to lead, but also to share views in creative ways such as photography, film, podcasts, art and blogs.

‘I was accepted for my opinions and they wanted to know more and what they could do’

Using social media as an outlet to get the message out to young people (as well as involve them in participation generally) is an obvious choice in a time when young people are so invested in it.

TikTok, Twitter and Instagram have sped up the ability to feed information back at speed and in engaging ways, as well as to larger numbers than other means of communication can reach.

However, there are extra safeguarding issues to consider when working online. A full understanding of these should allow professionals to capitalise on the benefits of social media, rather than fear it and therefore disregard it as a method of participation.

Some areas to consider:

A really comprehensive resource on this is provided by the NSPCC:

The firmest piece of advice is to have codes of conduct and online policies in place that protect both the young person and the professional.

So, for example;

Make sure that devices used by a professional are work-related rather than personal.

Make sure privacy settings are strong on ALL social media (young people will search and find you!).

For young people, what is safe for them to share and what is not? This may also vary dependent on the child (for example, those in care) so having very clear guidelines is important.

What are your procedures for dealing with safeguarding issues that arise? Having boundaries in any work with young people is vital, but with social media this is even more-so the case. For example, if a young person makes a disclosure at your work-place in office hours, there are clear policies to take that forward in the safest way possible for that young person. What if they tweet your service at 2 in the morning though?

What is your policy on monitoring content and comments?

There are easy ways to manage online forums and communities that can help this and, again, the NSPCC link is fantastic.

‘They listened to me and kept trying different tactics to help me get better’

Continue to the next chapter: Chapter 5 – Self-assessment and service evaluation